Having left Brazil myself several weeks ago, I had thought I wouldn’t blog again about it, but a recent string of shocking events compels me to revisit the matter. Rio de Janeiro, the city in which I lived, has in particular featured prominently in the turmoil. I thought I’d focus there in this blog post and then, in the next, pan out to give a broader view of what’s going on across the country.

Rio de Janeiro has found itself especially hard hit by economic crisis rocking the nation. It’s dependency on petroleum revenues meant it suffered badly from the fall in oil prices, which, by the beginning of 2016 had plummeted to their lowest level in more than a decade. Compounding the macroeconomic headwinds is the fact that the state oil giant, Petrobras, is still embroiled in an elephantine corruption scandal, the ‘Lava Jato’. Unlike some other Brazilian states, who made sure to stash funds away during the commodity boom years, Rio has not exactly been frugal, hosting both the World Cup and the Olympics, at considerable expense, in the span of just two years. The net effect is that the state (and city) is now seriously strapped for cash, barely being able to pay for basic public services (more on that later). The state university, UERJ, has been forced repeatedly to postpone the start of the school semester in response to what it calls the “largest funding crisis ever experienced in its history.” While students are frustrated at having to wait longer to complete their degree, most can’t help but sympathize with the striking teachers and other university employees, many of whom have not seen a pay rise since 2014, despite double digit inflation in the cost of living.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-632210003-575832ed3df78c9b46acd4d5.jpg)

It was against this backdrop of malaise that Rio’s citizens went to the polls in October 2016 to elect a new mayor of the city. Brazil operates a run-off electoral system for executive offices, which stipulates that if no candidate earns more than 50% of the vote during the election, a second election is held with just the top two candidates. The first round saw ten candidates put their name forward, including Javier Bolsonaro, the son of Jair Bolsonaro, the right wing demagogue whose shocking antics as a deputy in the national congress have earned him both ire and worship among different sects of Brazilian society. Given the fractured nature of Brazilian politics (no fewer than 25 parties have representation in Congress) everyone expected the vote to go to the second round, which it did, pitting Marcelo Freixo from PSOL (Party of Socialism and Freedom) against Marcelo Crivella from the little-known PRB (Brazilian Republican Party). The traditional party of the Left in Brazil had been the Workers’ Party (PT), but given that they had held the levers of power in Brasilia since 2002, they had fallen into disrepute in many people’s eyes by being associated (fairly) with the Lava Jato corruption scandal, and (less fairly) with the general economic downturn.

The Left, and young people in particular, therefore rallied around Freixo, a charismatic human rights lawyer, who campaigned on a platform of social inclusivity and more generous welfare programs for the poor. With his rustic, unshaven demeanor and disdain for formal attire, Freixo came across as every student’s favorite college professor. His platform and personality could hardly have been more different from that of his opponent and namesake, Marcelo Crivella, a stern-looking former pastor at the conservative, evangelical Universal Church of the Kingdom of God. Crivella’s religious background is infused deeply into his politics: he is a proud creationist who strongly opposes the legalization of both abortion and gay marriage. Evangelists command an enormous amount of power and wealth in Brazil, with many accusing them of preying on the gullibility of Brazil’s poor (Crivella’s church, UCKG, is alleged to have at one point sold ‘holy water’ to favela residents).

Freixo focused his rhetorical ordnance on Crivella’s religious intolerance and bigotry, a line of attack that gained some merit when a video emerged of Crivella delivering a sermon in which he stated that what “black people (negros)” liked above all was “cachaca, prostitution, and macumba (african religion).” At one of the head-to-head debates between the two candidates, Crivella tried to dismiss this accusation by claiming that in that video he was only talking about ‘black people in Africa’ and not Brazil – a rather bizarre way to explain away a racism charge, and, incidentally, not exactly credible, since the ‘cachaca’ he mentioned ‘negros’ being so fond of is a distinctly Brazilian liquor. Freixo doubled down on the attack though, and, perhaps wanting to prove that the words in this sermon were not simply the result of careless misspeaking, also cited a book Crivella had written some years back, in which, among other outrageous passages, the pastor had described Catholicism as a ‘demonic doctrine’ and homosexuality as a ‘terrible evil’. Crivella immediately issued an apology saying he was sorry “if he offended anyone” though quite notably did not explicitly retract the statements themselves.

Further plaguing Crivella’s public image was his perceived close association with the local ‘militias’. These lawless bands of armed men, often comprising active and former police officers, soldiers and prison guards, operate as what the New York Times termed a “criminal offshoot of the state”, extorting protection money from local residents, torturing journalists who try to unmask their illicit activities, and generally menacing anyone who stands in the way of their proto-fascist agenda. They hark back to the fearsome death squads that terrorized Latin America for decades during the Cold War. Freixo had made a career out of prosecuting these militia men, and so they naturally now resented him and his candidacy. As recently as 2012, one of these militia groups had murdered a judge in the driveway of her home after she had made a name for herself going after corrupt police officers. A family representative of one of the well-known militias (sanctimoniously named “the Justice League”) released a video pledging support to Crivella and defying Freixo to come to ‘their neighbourhood’. The threat, veiled as it might seem, was enough to prompt Freixo to hire extra security to follow him to all future campaign events. Crivella himself of course disavowed any support from the paramilitaries.

Freixo for his part suffered repeated criticisms not quite as dramatic, but no less damaging. Despite now standing as a PSOL candidate, he was lambasted for his past membership of the disgraced Workers’ Party (PT), and for his supposed socialist instinct to want to tax and spend his way out of every problem. His lifelong dedication to human rights was framed as his being ‘soft’ on crime, a major issue in Rio. Freixo was roundly mocked for suggesting, in a tweet, that the way to deal with Rio’s breathtaking high crime rate was not with more police officers, but with ‘more streetlights.’ As is often the case with politician’s soundbites, this one was sort of taken out of its proper context – namely, a more comprehensive plan to develop and illuminate public spaces in order to tackle some of the root causes of criminality. Freixo tried to tweet links to his full manifesto in a follow up, but the damage had already been done: “I’m heading to the favela with my expensive phone tonight”, one twitter user sardonically wrote, “but there’s no need to worry, since I’ll also have my lantern.”

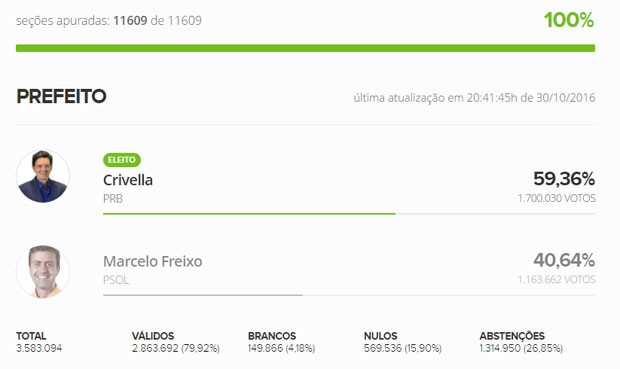

Nonetheless, Freixo continued to draw huge crowds at his rallies, and the enthusiasm in his campaign was palpable across the city. He also won the endorsement of such high profile celebrities as Wagner Moura, the actor famous for his portrayal of Pablo Escobar in the Netflix series, Narcos. In the end, however, Crivella’s well oiled campaign machine, with its army of dedicated evangelicals, won the day, earning 59% of the vote. A regional breakdown of the results revealed that Freixo, despite being the one advocating more generous welfare programs, in fact did best in the affluent Zona Sul districts of the city, cementing his status in the eyes of his opponents as just another ‘socialista de iPhone” – the Brazilian equivalent to a ‘champagne socialist.’

After assuming office on January 1st of this year, Crivella moved swiftly to make a series of controversial appointments to his administration. He tried to install his own son, Marcelinho, as chief of staff – a decision that was blocked by the Supreme Court, who described it unambiguously as ‘nepotism’. Worse still, he had to backpedal on an appointment to subsecretary after it was revealed that the man selected, Arthur Fuks, had made a series of incendiary and controversial Facebook posts, including one calling for criminals to be “turned into fertilizer” and another advocating life imprisonment terms for juveniles.

Crivella then ruffled feathers by refusing to participate in the opening ceremony of Carnaval, the city’s biggest festival of the year and the largest of its kind in the world. Traditionally, the mayor of Rio participates in a symbolic handing over of the keys of the city to the ‘Carnaval King’, an event which officially marks the opening of festivities for the week. For the many cariocas for whom Carnaval is the beating heart of Rio de Janeiro, Crivella’s flippant truancy constituted a shirking of responsibility as well as a total disregard for the city’s cultural traditions. Attentive political commentators suggested Crivella’s absence was a shrewd ‘political calculation’ meant to appease his ultra-conservative evangelical base, many of whom despise Carnaval as a hedonistic, Catholic lovefest.

Freixo meanwhile, far from slipping back into obscurity after his defeat, turned up again in February, this time spearheading a legislative fight to oust the governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Luiz Fernando ‘Pezão’, from office (whatever one might say about Pezão’s political integrity, his humorous good nature must be admired, having embraced his rather embarrassing sobriquet, which translates to “Big Foot”). Prior to his current mandate, Pezão had served as Vice-Governor under Sergio Cabral, and the two had been charged with operating a giant slush fund of corrupt campaign contributions, which they received from companies in exchange for lucrative state contracts. Cabral had already been arrested on November 17th of 2016 – an event which marked an ecstatic, watershed moment for many cariocas. Never subtle with his ill-gotten wealth, Cabral made himself into the epitome of Brazilian corruption. Considered untouchable, he lavished his wife (who was arrested with him as a co-conspirator in the corruption charges) with over 5 million reais ($1.5 million) in expensive jewelry; he resided in a swanky apartment in the ultra-wealthy Leblon district of Rio, which everyone knew had been bought with dirty money. Moreover he showed utter contempt for the city’s poor, once describing favela girls of child rearing age as ‘factories of criminals.’ No surprise then, that as he was hauled out of his building by armed federal police, crowds gathered at the scene to cheer on the officers. Within hours of Cabral’s arriving at the infamous Bangu prison in the West Zone of the city, his mugshots had leaked to social media. After a highly publicized and lengthy trial, Cabral was found guilty of corruption and, on June 13th 2017, sentenced to 14 years in prison. The millions of reais he stole were never recovered – the judge suspects that Cabral transferred the loot out of the country before being apprehended. Even so, that a man so wealthy and powerful had been humbled so low was historically unheard of in Brazil. It was another encouraging victory for the anti-corruption Lava Jato investigation. Pezão, for his part, managed to avoid a prison sentence, but was ordered by a judge to give up his gubernatorial position. For now he is defiant, vowing to take his case to the Supreme Court.

The next challenge for Crivella was what to do about the city’s appalling public finances. Due to a lack of funds, the Military Police, Rio’s main peacekeeping force, had not been paid since the end of 2016. Technically prevented by the constitution from going on strike themselves, the officers’ families threatened to block the exits to their precincts with their bodies, thereby preventing the patrol cars from going out on their rounds. Exactly this had happened a week or so prior in the neighbouring capital of Vitoria. The result was devastating. In just a few days of the police strike, the murder rate skyrocketed a whopping 650% with over a hundred people killed. Shops were looted, pedestrians assaulted in broad daylight, and cadavers left to rot in the street as public order vanished. Anyone who was able locked himself inside his home, sometimes for up to a week. The mayhem only abated when the army was called in to restore order. Rio’s population is almost ten times that of Vitoria, and already struggles to contain crime even with a fully active police force. Fear and panic therefore spread across the city at the thought of the police disappearing overnight. In the end, given that the mere anticipation of lawlessness looked to cause almost as much chaos as the strike itself, a spokesman for the military police, Ivan Blaz, took to local media to reassure the public that although small demonstrations had taken place, officers had still been able to leave their stations and that regular patrols would therefore still take place. The threat of strike had done it’s job though -Pezão immediately met with the head of state security and agreed to provide the police their back pay by the end of the week.

It was just as well that Pezão placated the police force as soon as he did. He was about to rely on them heavily as Rio got swept up in turbulent national protests against Michel Temer’s federal government. More on that in the next chapter!